Jerry Hutchens: Plenty first got involved in Haiti in 1975 when a famine in the northwest of the island, caused by drought and soil erosion, placed 300,000 people at risk of starvation. Much of the food sent by international aid organizations wound up for sale in the markets. Plenty contributed five tons of rice to the Mennonites’ “food for work” program at Albert Schweitzer Hospital in Haiti’s capital, Port-au-Prince. That presaged a stronger effort that would materialize four years later.

Haiti was, and remains, one of the poorest nations in the world. The dire predicament of the Haitian people was brought home to the crew of one of the Farm’s satellite communities in Homestead, Florida with the arrival of Haitian refugees in the mid-1970s. Michael Lee recalls, “There was boatload after boatload landing on the coast of Florida. People were coming in open boats, baking in the sun for thirty or forty days, dehydrated, coming to Miami. Just desperate to get off Haiti.” Most refugees waded ashore with nothing more than their wet ragged clothing clinging to their backs. They left behind the vicious hereditary dictatorship of the Duvaliers. First Papa Doc Duvalier, whose horrific reign left 30,000 Haitians killed or disappeared, looted the nation. His son, Baby Doc took over in 1971 and brazenly embezzled hundreds of millions of dollars from national coffers. Florida Farm folks kept running into Haitian refugees.

We made friends with a Haitian priest in Miami, Reverend Jacque. When asked how it was that the Duvaliers could stay in power so long, he looked grey, his mouth turned down. “Fear,” he said.

The Haitian boat people were largely illiterate and spoke only Kréyòl, a fluid mix of West African languages and old French that only other Haitians (and Plenty volunteer Randy Scovil) could decipher. The Florida Farm began helping the refugees find food, work, and housing. We took refugees to jobs picking tomatoes and squash in the Farm’s school bus. We found a few more permanent work and moved a refugee into our home. The realization came that the best thing to do would be to improve the situation in Haiti so that people did not feel compelled to risk their lives traveling to a foreign land. How to do that?

In 1979 a brief news item appeared highlighting the work of Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity with the poor in Port-au-Prince. This generated interest among the farmers and families on the Florida Farm. We were already familiar with the Plenty Ambulance Center and its relationship with Mother Teresa’s Sisters and the selfless work they were doing in the South Bronx. Was there a possibility of helping in Haiti?

The Missionaries of Charity also had a group of nuns in Miami. A phone call to them got the Sister’s address in Port-au-Prince. Michael Cook wrote a letter to the Sisters, “We are willing to help. What do you need?”

Michael Cook: They said, “We have malnourished children and we can use diapers and supplies.”

They gave us a list of what they needed and we packed up a bunch of that stuff and sent it over.

They got back in touch with us and said, “That was great.” We talked to them on the phone and we asked, “What else do you need?”

They said, “Oh, we need seeds for a garden.”

We said, “That will be no problem, we’re farmers and we can put that together.” They said, “We would love to have the seeds and the tools, but what we would really like is to have somebody come down and plant the garden. We’d like you to come and do it.”

We said, “Okay. We’ll think about that.”

The primary purpose of the Florida Farm was to provide vegetables and income for the Tennessee Farm. To raise money for the trip to Haiti we got agreement with the Florida Farm and the Tennessee Farm, that we could keep part of our roofing company money to fund the project for Michael Lee and me to go down and put in the garden.

We didn’t have to get visas. I don’t think we even got shots when Michael Lee and I went down the first time.

We brought the Sisters a rototiller. That was considered a ‘machine’ so Haitian customs wanted to impound it and hold it for a couple of weeks. We were only going to be there for a couple of weeks. That wasn’t going to work for us to do the garden. There was a Sister there, Rakini, who was in charge of getting through the customs. Sister Carmeline sent us back with her. A guy at customs, six-foot three or four, much bigger than me, huge build, dark sunglasses — border patrol vibes, Tonton Macoute (Volontaires de la Sécurité Nationale) for sure — was telling us, “It’s going to take a while. It’s machinery. We have to…” Sister Rakini interrupted, “No. We have to have this equipment.” He may possibly have been looking for a bribe, but the Sisters didn’t do that. She read him the riot act. She said, “You have got to figure this out. We are coming back and picking this up tomorrow.” And they did. The Sisters had a lot of people who were backing them. Besides the rototiller, we brought tools for working the soil and got together a 3/4 acre garden with beans and vegetables.

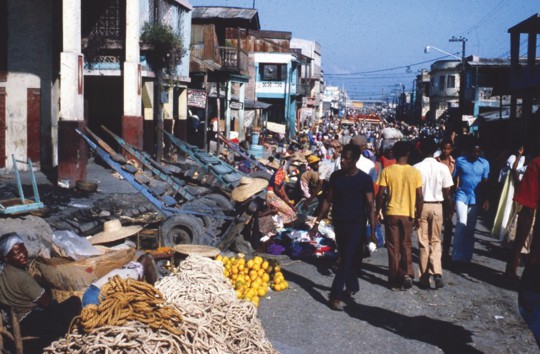

Michael Lee: We stayed in the ghetto with the Sisters the first time we got there. They said to go out and take a walk — “Go on. Go walk around.” We were in downtown Port-au-Prince. So we took a right-hand turn and went down towards the docks. It was absolutely the worst section of poverty in the city.

A lot of the kids were not clothed well. An average house was just a few pieces of tin, rags, and some cardboard in a big mud swamp. Now the police don’t even go in there. It’s ruled by gangs. Having grown up in the suburbs and not having traveled the Third World much it was fairly overwhelming. We were idealistic, but we were learning.

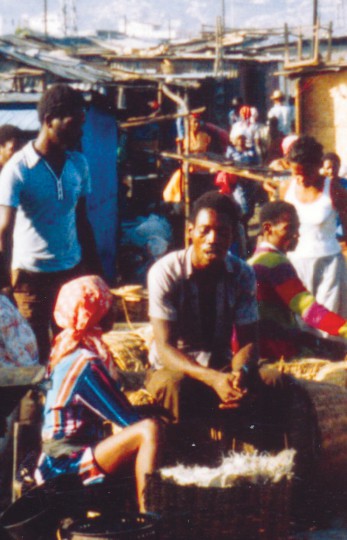

There was a real sense of pride in people’s individuality, even though there was the other extreme where people had half-human lives. People called their businesses the English word, “commerce.” They’d be selling whatever. There would be little things, like one meal’s worth of charcoal on a blanket with somebody sitting there and people would buy it just for a meal.

The Sisters’ Home for Dying and Destitute was a couple of buildings, surrounded by a big seven or eight-foot wall. On the top of the wall they’d set broken glass in concrete, pointed up, so people couldn’t climb over. They had armed guards patrolling at night. To be sitting on top of that much food put them at risk. When we lived there, the food would come in once a month. We’d go down to the docks to pick it up in a three-ton truck. We’d load up all the grain and then we would have to hire three or four people with sticks to beat the crowds off. People would run up to the sides of the truck trying to snatch bags of rice while we were transporting them back to the compound.

The Home for Dying and Destitute was a catalog of diseases. This was the late ’70s, early ’80s, before we knew about AIDS. But there was lots of tuberculosis and all kinds of diseases. Once I was out back doing some cleanup when the ground gave way and I collapsed into the leaky septic system. As I went sinking in my leg ripped open on a rusty piece of metal. I got out, went inside and put boiled water on it, put antiseptic on it, and just hoped for the best. It was a kind of initiation.

Michael Cook: The water went out at the Home for the Dying and Destitute. This is an issue. There was diarrhea, and ninety men and women, in two different dorms. Michael Lee and I came up and said, “What are we going to do today?” And Sister Abba said, “Ho. Ho. Ho. Well, guess what? There is no water. Ha. Ha. Ha.” She was cracking up. We asked, “What do we do?” “Well, we going to get a rain,” she joked. The building’s cistern was usually filled with rainwater. But it turned out, that the reason the water was not coming through was that young teenage boys had decided a good way to cool off would be to slip into the cistern, and they had accidentally broken the arm of the float that let the water come in and out. The teenage boys had been swimming in the cistern.

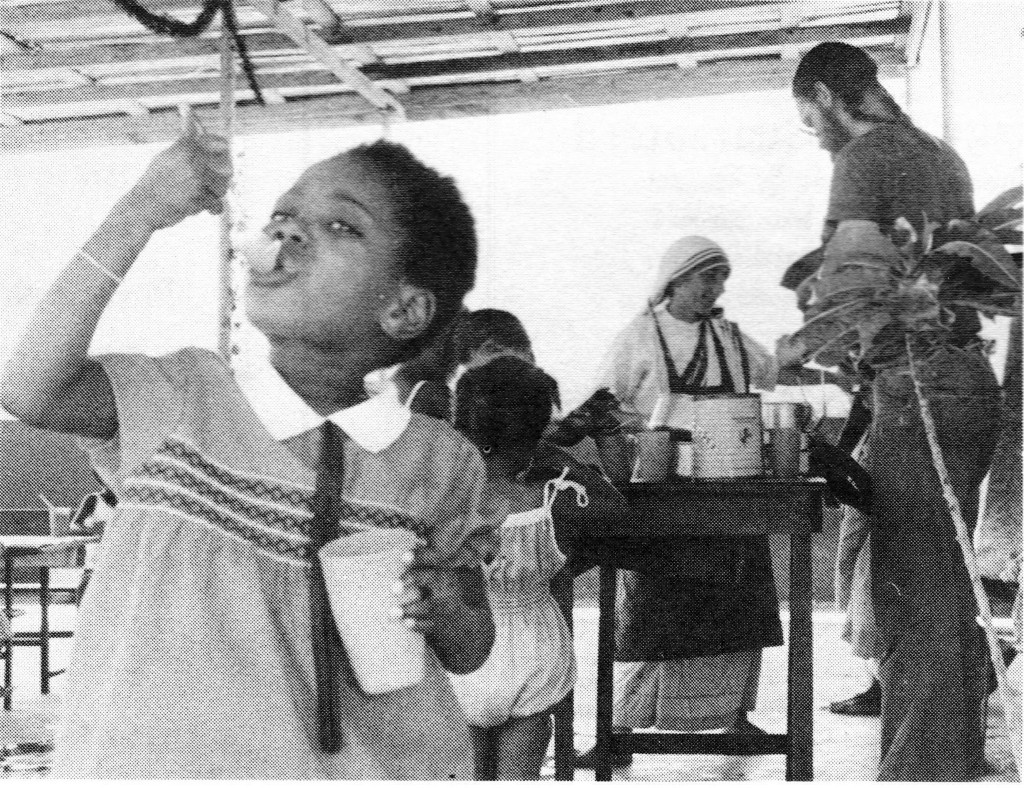

The Sisters also ran a Home for Malnourished Children. It wasn’t so much an orphanage. They mostly took in kids, got them fixed up, and gave them back to their parents. The Home for Malnourished Children had lots of beds. It was a big house a rich Haitian man built for them. He built it originally as quarters for the nuns to live in while they were getting the home together for destitute and dying women. Then Mother Teresa visited and said, “This is way too nice for you. Build a little place for you down the hill. This house can be the place for malnourished kids.” Each of the Sisters had one bucket of water each day and that was what they washed with and washed their clothes in. They each had two saris. Even though they put in running water, that was what all the Sisters did everywhere, so that is what they did. They were frequently being shipped to different places, so they knew the routine and they could survive on that much stuff. It wasn’t an adjustment — it was how they lived. They didn’t want people to get too attached. They rotated everyone who was in charge too.

Michael Lee: The Sisters were very jovial — a lot of fun to be with. They had Sister Carmeline. She was the keeper of the order and was more like a drill sergeant. Sister Carmeline was about five feet tall. She didn’t start out as a Missionary of Charity — she had been in another order for a long time. You could tell she came from the old school.

I remember one story about Sister Carmeline. They call it the General Hospital there in Port-au-Prince. Whoever wanted to stay there, it cost a dollar a day. If you didn’t have the money they had a cinder block building where the hospital staff would take you down and just leave you there, no matter what condition you were in. The Sisters would go there and pick up people, and bring them to the Home for Dying and Destitute, and give them proper care for their passing.

The ambulance would come from the hospital to the Home and take the Haitian bodies that had passed away. We would average about one every other day. The hospital staff got thinking, “If the Sisters are taking them anyway, instead of hauling people to the concrete bunker, we’ll just take them straight to the Home for Dying and Destitute.” That would save the Sisters the trip of having to go and pick up the patients. One day we were there and the ambulance comes with a doctor and a nurse to pick up a dead person. At the same time, they brought four patients for the Home for the Dying and Destitute. Sister Carmeline said, “Don’t bring us any more people.” The doctor said, “Why not? You go every day to pick them up.” She said, “Yes, but we don’t put them in there. If you are going to put them in there — I’m not here to relieve your conscience — you put them in there and I’ll deal with it.”

Michael Cook: After two weeks, when we were ready to leave the Sisters said, “Please come back. Bring your families. Stay longer.”

Getting back to the Florida Farm we said, “We want to go back.” The Florida Farm had a meeting to decide if it was okay for us to do that. Could some people keep making money to do it? Everybody decided, “Yeah, it would be a good thing to do.”

We raised the money for the tickets. Then Plenty supporter Pat McCarthy sold her engagement ring and Margaret’s sister, Mary Hamilton, sold her wedding ring. They got $500 for the rings and that paid for Haiti living expenses.

Margaret Hamilton: “We really thought we had a lot of money — five hundred dollars!”

Michael Cook: We landed with our whole kit and caboodle and five hundred bucks. Sister Carmeline arranged for us to stay with a family, a Canadian woman married to a Haitian guy. We got there, she showed us around the house, and it looked really good. Then her husband came home and talked to the wife. We asked, “How much is the rent?” And he said, “Five hundred dollars a month.” We turned to Sister Carmeline and said, “That’s all the money we have. This is not going to work for us.” She said, “That’s not a problem. Stay here.” She left and was gone about ten minutes and then came back and said, “Get your things and come with me.” We walked out the front door. Walked down the driveway. Walked down the road to the next corner where a big guy with a machine gun is standing. She walks us by him and into the house and said, “Here he is. This is the Mayor of Port-au-Prince.” He was standing there in front of us and could hear Sister Carmeline say, “I told him, no I demanded — you are going to stay with him.”

Margaret Hamilton: The Mayor had been big in the government of Papa Doc. When we were there, Haiti was under Baby Doc. But this guy had been in there with Papa Doc. I always assumed that one of the reasons he let us hippies move into his house was because he was getting old; he was dying and trying to make peace with God and wanted to do good, to get straight with God by helping Mother Teresa’s nuns.

Michael Cook: Before we got to Haiti Margaret was calling Sister Carmeline because our daughter Emily was real little; she was in a low percentile in terms of her body weight. Margaret was explaining, “I’ve got this scrawny little kid and I’m worried about her living in Haiti.” Sister Carmeline said, “She is a healthy American kid. Don’t even worry about it. Just bring her over.” We showed up with Emily and they all said, “Oh my, she is really small.” But they were the experts at feeding malnourished children. They loved her and just took her in and she gained weight in Haiti! They were feeding her nutrition biscuits, with protein and fat, fresh from England. The Sisters loved her, saying, “She would make such a good little nun.”

Michael Lee: The Sisters would let us go to their nice place to baby-sit our kids. We tried to minimize the kids’ exposure to everything. We took extra precautions to keep our kids out of the mainstream. Like if you went down into Port-au-Prince, down off the side of the mountain where we were, you could see a solid cloud of dirt, dust, and diesel fumes that we were immersed in. We tried to avoid taking the kids down into that. The kids were sheltered to some degree from the general conditions.

Michael Cook: Margaret and Mary worked full time at the walk-in clinic. When they first got there, Margaret asked the Sisters, “Who does the diagnosing?” The Sisters were hopeful, “Do you know how to diagnose?” The Farm Clinic training was excellent. The Sisters were good at tuberculosis and leprosy. They had those down. They knew how to test for those. They could recognize them. They knew leprosy as soon as they saw it. Things like kids with ear infections were a problem.

Margaret Hamilton: I was an EMT (emergency medical technician) and a Paramedic before I went to Haiti. I wasn’t trained as a nurse, but I had worked in the Farm Clinic examining kids. So I took my otoscope, for seeing the outer and middle ear, to Haiti with me. The first day the Sisters took Mary and me to work with them in the clinic, a girl came in saying, “My ear really hurts.” I took out my otoscope and could see the patient had a perforated eardrum — a big hole in her ear. There was a doctor in the clinic that day who had been sent there by Baby Doc. It was like the Doonesbury comic where he talked about the “Baby Doc College of Offshore Medicine.” I wasn’t licensed to prescribe medicine so I asked the Sisters if we could take the girl back to where the doctor was. They said, “Yes.” We walked back to the small room where the doctor was working. The nun told the doctor what was going on so the doctor took out his penlight and used that to try and see into the ear. It wasn’t working that great so I handed him my otoscope. He looked at my otoscope like, “Oh my gosh. What is this?” The doctor held the ear at arm’s-length with the otoscope pressed against his eye. He did not know what an otoscope was or how to use it. I thought, “Whoa. I don’t want too get sick while I’m here.”

There was a baby at one of the clinics that was just bones — looking like it was going to die. The mother came to me so concerned and I gave the mother some formula. Then other mothers got really upset that I had given one mother some formula and their babies needed help too. “What about our babies?” Their babies were not as bad but the people were desperate. I hadn’t realized I could get in trouble by helping a baby.

Early on, a patient came in with a bad infection. I told her to wash it good with soap and warm water and put warm compresses on it. A nun there asked, “Where are they going to get warm water?” I had no idea. There was a lack of the most basic things.

Michael Lee: There were a lot of infections. You see people with raging infections just going along. Eye infections, feet and hand infections. It was a cultural shock to be there and see it.

Margaret Hamilton: We were giving lots of penicillin shots and other sorts of shots. We were using thick old needles. I accidentally got stuck a few times. At one point I asked, “Who is sterilizing the needles?” The Sisters pointed out a small dirt-poor Haitian lady. It kind of set me back, because I didn’t feel certain about how she did it. How well were the needles boiled to sterilize them? She would buy little piles of wood in the market, so if she wanted to save money, to use the money for something else, who knows? Maybe I was infecting people.

Michael Cook: We had sent over equipment for a dairy to show the Sisters how to make soymilk. We’d asked them what they wanted us to bring and they’d given us the usual list of things that we got together. They said, “There is one other thing we’d like you to bring — statues.” They are Catholics, you know. Margaret and Mary went to the local Catholic Church in Florida and asked, “Got any statues we can take to the nuns in Haiti?” It turns out they had just replaced the statues in their church and they had a stash. They had a plaster Joseph, a Mary, and a Jesus.

Then we had to get crates to protect them during shipping, along with a big kettle for cooking the milk and all the soybean grinding equipment, and the rest of the set up for the dairy. Each statue had to have its own crate. They were three or four feet tall.

We got to Port-au-Prince and were waiting for our stuff when we learned the boat had stopped and left without unloading our equipment. The boat was on a Caribbean route and we had to wait for it to come back around. When we finally delivered the statues, the Sisters were so happy. It was like Christmas for them. One statue had a small broken place on one of its fingers. They said, “That’s no problem. We can find somebody around here who can work plaster to fix that.” They put Joseph in the men’s ward.

In the Home for the Dying and Destitute there were all these flies. We said, “We’ve got some money. We’ve got some time. Just take us to the hardware store.” We bought lumber and screens for windows. We made the frames, stuck the screens on, and put up the screens. None of the people in there had ever lived with screens before. Then we went around with fly swatters and swatted the flies and the fly population started to drop, and they began to realize what it was like to not have flies landing on you when you are out of it and lying around sick. They started to get into it and started going, “Yeah!” and whacking flies. It was a big fly whacking celebration. Screens made a difference right away.

Margaret Hamilton: I wanted some home-cooked soybeans, and wanted to show the Mayor how great soybeans were. We didn’t have a pressure cooker ring for the pressure cooker we wanted to cook soybeans in. We finally got a used ring from one of the people down there, but it was a rotten ring. There were two kitchens in the Mayor’s house — a Western style kitchen on the second floor and an open fire wood burning stove downstairs where the servants cooked for the Mayor. While the Mayor and his wife were out, I was cooking in the upstairs kitchen, fixing soybeans in a pressure cooker with the rotten ring — not realizing the danger. I was sitting at the kitchen table when the pressure cooker flipped off the stove and exploded.

Beans splattered all over the ceiling. I thought, “This is not good.” I jumped on a counter with a spatula and started scraping beans off the ceiling. One of the servants rushed in and she started scraping beans off the ceiling. As I’m scraping I hear people coming in the door. I look down and see the Mayor, his wife, the bodyguard with his gun, and another couple. If something bad was going to happen — this was the moment. Fortunately the other couple was there; I think that kept the Mayor’s wife from getting too uptight. They just wanted to know, “Did any body get hurt?” They were real impressed with us.

We brought our microscope to Haiti. While we were at the Mayor’s house, behind closed doors, I was looking at shit samples. No way did they know. It would have really freaked them out. We weren’t going to talk about that.

The former Mayor was old, crippled up, and arthritic, but very nice to us. This was one of the sacrifices he made. I can see him telling God, “I let those hippies move into my home. They were looking at shit samples and blowing up pressure cookers.”

Michael Lee: One of our grand finales there, just as we were getting ready to set up the dairy, was when we got dengue fever. Another name for it is break-bone fever. You feel like every bone in your body is broken. You cannot do anything. We’d moved out of the Mayor’s house and we were living in a place that had a mosquito problem. The mosquitoes infected us with dengue fever. Margaret and Mary were the first ones to come down with it. They were really, really sick.

We were lucky the kids didn’t get it because it could be the end for kids, ya know. I was so sick with the fever I was lying naked on a mat, when the Cook’s son Chris opened the door, and all the Sisters were standing there looking in. They thought that was hilarious.

Michael Cook: The dairy equipment came. We were getting ready to set up the dairy when Mary came down with dengue fever. Then Margaret. Then Michael Lee, who had been taking care of them, went down. The kids were okay but I was getting nothing done. All I could do was take care of kids, take care of sick adults, and try to find things they could eat. They had high fevers and were sick to their stomachs with not much appetite. The project was no longer moving along, so we decided they should all just go back to the States. Take the kids, get out, and leave me. Michael Lee was still extremely out of it. We were like, “Okay. When you get to the airport, you have got to at least be able to stand up at a few critical moments and act normal. We don’t want them to not let you on the plane.” We had Michael Lee propped up against a light pole in the airport.

Michael Lee: Michael Cook got us to the airport, got us to the plane, and when he got home that night he started to throw up and have the runs.

Michael Cook: So they left. This is the point where I got sick and thought I had dengue fever but it was only food poisoning. That was a relief. I was well within twenty-four hours and was able to finish getting everything set up. The Sisters were making soymilk and soy ice cream by the time I left.