David Purviance and Jeanne Kahan (plus their three young children) and another couple, David and Michele, made an agreement to do a Plenty project in Bangladesh. David and Michele went first and volunteered at a hospital for destitutes run by Dr. Jack Preger in the Kamalapur slum of Dhaka. The David and Jeanne arrived a short time later.

Plenty was only three years old when it came near to the time we were scheduled to leave for Bangladesh. As a small and largely untested organization, it was hard to find donors willing to sponsor its programs. Over time Plenty built up a base of loyal supporters who contributed to the unique projects we administered, but for the first few years it was primarily the Farm that underwrote many of Plenty’s projects. Our Canadian ally in Guatemala, CIDA, covered most of the expenses for that effort, but the Bangladesh project had no such donor. Funds were tight and Plenty was never able to send as much money as we requested. We jokingly characterized Plenty’s support for us as a one-way ticket and a parachute. And it was not far from the truth.

After some training by Jack Preger in treatment of the diseases they routinely encountered, along with a crash course in what medicines were available, and a few lessons in dealing with the Bangladeshi staff he had hired, Michele took over the hospital. What a shift from the U.S. where a nurse would never make a life and death decision or even prescribe a medication without a doctor’s input, to the Kamalapur clinic where Michele diagnosed, prescribed and treated almost every ailment coming in the door. Jack would double-check her decisions for the first few months, but soon she was on her own most of the time.

This was life and death stuff, and more than a few patients died while in the hospital, their diseases having progressed to the point where recovery was impossible. In those cases, Michele did what Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity did with their dying patients: she sat with them, held their hand, gave them her love, and eased them through their death.

Any disease in the world could walk through the hospital doors, and Michele (with Jack Preger’s help) had to diagnose without benefit of laboratory tests or modern equipment. The hospital had a small pharmacy, but no diagnostic laboratory. The medical equipment on hand was limited to a few basic devices that could be carried in the pockets of a doctor’s smock: stethoscope, ear-and-throat otoscope, thermometer, tongue depressors, etc. If this sounds primitive, consider the alternative for these people: dying on the streets without any medical care whatsoever and no medication either for healing or for easing the pain as death approached.

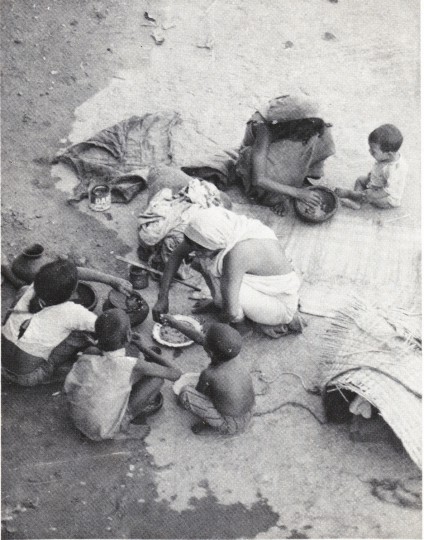

The hospital was located next to a railroad staging area, where freight trains were assembled and disassembled. As the world’s most densely populated country (120 million people in an area the size of Wisconsin) Bangladesh had no room for the landless peasants. Those people who were forced into the city because of drought, overwhelming debts, death of a husband or, for children, the deaths of their parents, had no place to live. They gravitated to areas that were no-man’s land, such as the railroad tracks. Here they either erected makeshift shelters the size of a backpacking tent from scraps of plastic and cloth, or they merely lived under the numerous boxcars parked on dead-end railroad tracks for later use.

The hundreds of destitutes living along the tracks just a few feet from the hospital had many needs and over time Jack’s clinic tried to address most of them. On many occasions women dressed in filthy and threadbare saris with matted hair and skin caked in dirt would enter the hospital in the late stages of labor. Michele, who had never delivered a baby before coming to Bangladesh, became the midwife for many destitute women.

Whenever you visit a developing country for the first time, especially one in the grip of overwhelming poverty like Bangladesh in the mid-1970s, your first day is absolutely unforgettable. All your senses are bombarded by unfamiliar and often jarring sensations. The tidy and sanitary environment of the West is nowhere to be seen. The incongruity of what you absorb paralyzes the mind. Looking like beautiful, tropical flowers, the women in their multi-colored saris are seen stepping around the filthy, nearly naked bodies of mutilated beggars. The smells of delicious food served in roadside stalls intermingle with sweet incense and excite the olfactory nerves, until one passes an open-air butcher shop or a wall that serves as a male urinal and then the stench is nauseating. Seemingly unattended cows and water buffaloes share the busiest roads with motorcycles and cars. Attempts at creating eye-pleasing gardens and natural beauty in roadway medians and public parks are drowned in oceans of garbage and litter.

There was no home-cooked meal prepared by Michele awaiting us when we arrived from the airport. There wasn’t even Michele awaiting us. As we were to quickly learn, she spent 10 to 12 hour days at the clinic and was often called back at night for an emergency. She was unable to leave the clinic even to welcome us to Bangladesh. Leaving the kids with David, Jeanne and I walked the 200 feet from our apartment building to the warehouse next door that served as the Kamalapur Clinic.

It was a scene we would see hundreds of times over the next two years, but that first visit was truly staggering. In a large bare room we saw row after row of simple, wooden cots, covered with thin, straw mats. The beds, spaced two feet apart, each supported a human body that looked ready to die. Some were emaciated frames, with protruding bones thinly covered by flesh, like a gauze cloth draped over a skeleton. Others had stomachs that were distended, making elderly men look like pregnant women. A few were blind; some were missing arms or legs. Several of the faces staring at us had the telltale signs of leprosy — missing ears and noses. We could see horrible sores and lesions oozing liquid on legs and arms. One man coughed uncontrollably and leaning over his bed managed to dislodge bloody phlegm into a pan on the floor. Coughs and wheezes and an occasional groan were the only sounds these 55 invalids made as we walked past them to the far end of the room where Michele was examining a patient.

In the months prior to leaving for Bangladesh we had tried to emotionally prepare ourselves for the shock of this moment. We knew it was a Mother Teresa type mission we were undertaking and death and suffering would be our daily companions. But imagining it is one thing; seeing it first hand was staggering. Inwardly we recoiled from the horror we were witnessing. Almost every disease imaginable was present in that room. Our knowledge of microorganisms and how they spread told us that every oozing sore, every cough and every sneeze sent deadly viruses and bacteria into the air we were breathing. And just as paroxysms of fear started to overtake us with the realization of what we had gotten ourselves and our children into, Michele did the one thing that could put us at ease. She reminded us that these were people first and patients only incidentally.

“Now this is Mohammed,” she said, walking over to one bed that housed a skeleton of a man.

“Actually almost all these guys are named Mohammed. That makes it easy to remember names,” she laughed. “Mohammed, bhalo achhen (How are you)?”

The man smiled at Michele and replied to her Bangla query in a string of words we could not understand, but she seemed to follow it all.

Moving to the next cot, she introduced Saleem, a man whose leprosy had claimed parts of his face. “Salaam Saleem,” (Peace Saleem) she said with a laugh at her poetic greeting. Saleem smiled at Michelle, seeming to appreciate a joke he had probably heard a thousand times in his life. Salaam alaykum (Peace be upon you) was the standard Muslim greeting, I later learned, to which one would reply wa ‘alaykum al-salaam (And unto you peace).

“And this is Mohammed number two, or is it number three or four?” she asked rhetorically at the next bed. The man had a grotesquely large bulge in his abdomen. He was obviously bloated, not fat, as his pencil thin arms and legs attested. Michele reached down and patted the man’s protruding stomach.

“We tease Mohammed that soon he will be famous as the first man in history to give birth. If we could just figure out how to get the baby out of there.” She laughed again and said something in Bangla to Mohammed who laughed in reply.

And so it went with person after person. Michele humanized the situation for us. She knew better than anyone that contagion surrounded her — that any surface in that room probably harbored the planet’s most dreaded organisms. But she also knew that some of these people would not survive their illness despite the best efforts of herself and Dr. Preger. They needed love not revulsion. So she refused to let fear guide her reactions and instead used her humor and rural Kansas earthiness to help her patients forget the seriousness of their condition. It was a lesson that stayed with me the entire time we lived in Bangladesh.

I was happy, after returning from Bangladesh, to see old Farm friends again and to be back in my native land. There was an easiness about being in America that was lacking in Bangladesh. But something had changed in me over the previous two years. The comfort of being back in the land of plenty was offset by the personal knowledge that billions of people could not live like Americans do. I had to leave the Third World, but the Third World would not so easily leave me. The opportunity Plenty had given me was something that changed my life forever. It was both a gift and a burden. Years later I spent five years living in India where I helped the victims of the 2004 tsunami and started a charitable organization to work with destitute women and children. Today my charitable work with World’s Children takes me to India and other developing countries frequently. It’s the fruition of a tiny seed planted in my soul years ago when I accepted a one-way ticket and a parachute and took a journey from which I never returned.

<><>><<><>

An unusual incident happened one day when Jeanne and I were in Nashville. Plenty had managed to scrape together a couple hundred dollars to send to David and Michelle. It wasn’t as much as they wanted, but it would help. We were in Nashville solely to wire the money to them. As we walked through the business district toward the Western Union office a limousine pulled alongside us and stopped. One of the darkly tinted windows rolled down and an older man extended his hand toward us. In it was an envelope.

“Here,” he said, “take this. I’m not sure why I’m giving this to you, but God just told me you’re supposed to get this.” I could understand his puzzlement over this directive from God. Jeanne and I were two full-blown hippies with all the trappings: Long, braided hair, unkempt beard, tie-dyed tee-shirt and patched jeans for me, and what might be described as Russian peasant attire for Jeanne. He probably ruefully thought his gift would be used to purchase drugs.

I looked in the envelope and saw a fifty-dollar bill. “I know why you gave it to me,” I said to the man. “We’re on our way to Western Union to wire money to our friends in Bangladesh who are helping to save the lives of destitute people living on the streets. This money is for them, not for us.”