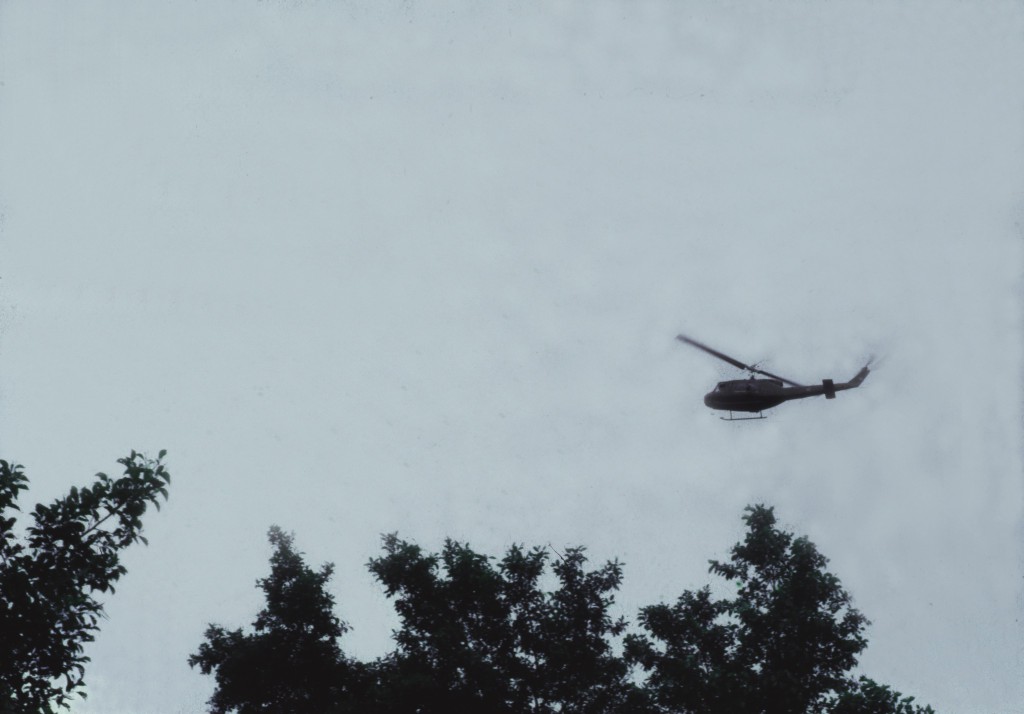

In December of 1979, our illusion of security in Sololá was shattered as Guatemalan Army helicopters swooped in low over our village, bringing wounded troops to the local hospital from a guerrilla ambush in the mountains only ten miles west of us. Reports varied from the Army’s official count of “four dead” to third-hand rumors of over twenty soldiers killed in the encounter. To the guerrillas it must have seemed a great success, but it was a spark that touched off an increasingly brutal exchange that ultimately forced Plenty to leave Guatemala.

The helicopter incident shook us up, bringing some of the reality of the ongoing 30-year civil war to us in a flash, but after some days of consideration, we decided to continue with our projects. We had not been directly threatened, and, as it turned out, we never would be. The actual fighting was contained at a safe distance in the rugged mountains at the west end of Lake Atitlán. Had it not been for our proximity to the provincial hospital, we might never have crossed paths with the incident.

So, over the next six months, we concentrated on the implementation of our projects — the soy dairy, our agricultural work, our water projects. We knew that our stay in the country could easily be cut short by circumstances and events over which we had no control, and Guatemalan newspaper accounts served as our barometer of the worsening situation throughout the country. For those of us used to news reporting in the U.S.A., where brutal crimes are given special, prolonged attention and headlines, it was strange to read Guatemalan accounts of the daily atrocities listed in the papers like small wedding announcements, treated almost casually and never followed up by investigation. Common fare: mutilated bodies found in a ditch, signs of torture, often unidentified or unidentifiable, crime committed by “unknowns.” Obviously, when push came to shove between the Establishment and the perceived Anti-Establishment, life was cheap. And yet, our work and the work of many others there was aimed at enhancing the value of life. It was only a matter of time before these two value systems would clash. What would happen?

Summer of 1980, following the Republican Convention in Detroit and Ronald Reagan’s nomination, events accelerated noticeably in Guatemala, and we began to be touched by them for the first time.

In our projects, we included many local villagers who worked and trained with us. One of them, a very intelligent and kind fellow named Justo, was helping us on our three-village water system. He had worked for other groups before Plenty, and was an experienced water systems technician. He did most of the fieldwork for us, supervising, measuring, and installing the 19 miles of pipeline in the gravity-feed system. We paid him well by Guatemalan standards — $10 per day.

One day he came to me, looking pale and ill and shaking. He told me that he had heard that he was on The List. To be on The List in Guatemala is to be a marked man — a candidate for torture and execution. Justo was educated and had been active for some time in projects helping the poor, organizing the people in self-help projects. In the eyes of those who made The List, he was a potential revolutionary who had to be neutralized and put out of action. His wife pleaded with him not to come home where he would be a sitting duck. Bodies of people that he knew well began being found in roadside ditches — calling cards of the Secret Anti-communist Army and the White Hand — warnings to others on The List. Following my first impulse, I told Justo that he and his family could stay with us until we could figure out a safe place for him, his wife, and three children. We moved them in the next day. They were still full of fear but visibly relieved. Their stay was to be a short one though, because, in consultation with Plenty headquarters, it was decided that Justo’s presence might draw the threat to ourselves. Government “orejas” (ears) were present everywhere in Guatemala, and our continued safety could not be taken for granted.

When I told Justo that we could no longer provide him sanctuary, I began to weep. He made it easy on me, though, telling me that he fully understood and that he had wondered himself if his being among us was dangerous for us. So Justo and his family moved back to their village where he continued to sleep outside of the house each night, sometimes in the woods, sometimes in the cornfield and, when it rained, in the hog shed.

At the same time, we had been pursuing a long-standing agreement to help two other villages get water systems. Both of them lay to the west, in the direction of the troubled area. The systems had been measured and designed, and there was money available. Many of the people had lost children to various diseases that came with unsanitary or insufficient water supplies. They saw Plenty as perhaps their last chance to improve their condition since the political situation was deteriorating rapidly around them. Teodoro Yac was the president of the Village Improvement Committee. He was smart enough and successful enough to be a farmer and a businessman that owned the only truck in the village. He had organized the village men in the construction of a new road, and he would organize them for the installation of the water system.

On a Saturday in August, Teodoro came by with his fellow committee members to pick up the completed plans for the system, which he would use to help solicit more funding for the system’s reservoir. The next morning four men dragged him from his house. As they threw him into their car, they machine-gunned Teodoro’s truck. A week later his body was found by the main crossroads. I knew him. He was no guerrilla. He was a farmer who believed in striving for success for his family and his community.

Over the following weeks, it became increasingly difficult for us to pursue our work. Helping people meant putting them in positions of responsibility. It meant holding meetings. It meant, in some form, organizing. But it had also come to mean making obvious targets of the people we were trying to help. Soon, the leaders from the villages to which we had helped provide water came to us pleading for us to take them to the United States. They, too, had heard that they were on The List. We knew we were going to pull out soon, but we tried to keep the word from getting out. It was a hard secret to keep, impossible, in fact. It became so difficult for us to continue our work, and at the same time deny sanctuary to those who needed it, that we decided that it was time for Plenty to leave Guatemala. We told headquarters over the radio, “Come and get us. There’s nothing more that we can do here.”

The day before we left, Justo came to say goodbye. He described how he would sit and watch the road entering his village — watching for strange cars and unfamiliar people. I left him my binoculars.

Peter Schweitzer: This story raises one of the most agonizing decisions Plenty ever had to face. In retrospect, most would agree, we had no choice other than pulling our volunteers out of a situation where their presence could be seen as making targets out of the communities we were helping, and there was an increasing threat that one or more of the volunteers could be killed. We have been asked why we didn’t stay and protect our friends. One answer is that we were responsible to the families of our volunteers for their welfare. We were not sending people to Guatemala to be martyred. Our volunteers did not go to Guatemala to stand between the guns of madmen and the helpless Mayans. We would not ask them to do that. That is also a choice we could not ask them to make in Guatemala. So we brought everyone home and began to work at making our government and the people of the United States aware of what was going on. Even that effort, ultimately, had to be curtailed because it might endanger people who had worked with us and it might prevent us from ever being able to work with them again.